The Half-Life of Propaganda

As war in the Donbas region grinds on, the Russian military is in desperate need of fresh troops. From central Russia to the far-flung provinces, reservists are being called up and, in many cases, sent to the front [1].

Along with these official summons, Russian citizens have been subjected to broad-based propaganda campaigns, which extol the virtues of military service and downplay casualties. At FilterLabs.AI, we have been measuring the efficacy of these campaigns in Buryatia, a province on the border of Mongolia. Our findings reveal something about the limits of propaganda, and how to defeat it.

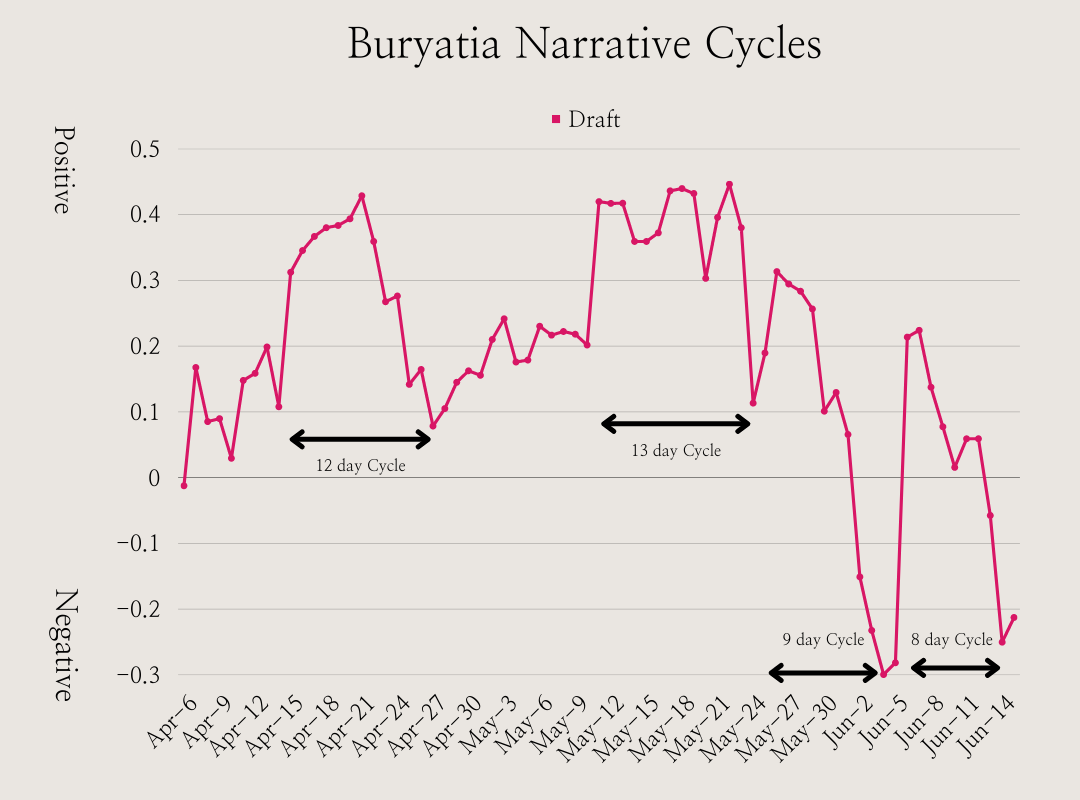

Looking at a chart of local sentiment toward the draft, it appears that the Kremlin propaganda runs on 9 to 13-day cycles. Between mid-April and mid-May, sentiment toward the draft rose significantly. However, the effects were short-lived, and Kremlin efforts to boost support for the draft became less effective over time.

Despite periodic boosts in sentiment in favor of the draft, the overall trendline is sharply negative, suggesting that propaganda has diminishing returns. There are several reasons this might be so. For one thing, as people hear the same messages again and again, they may tune them out.

Propaganda also becomes less believable if it plainly contradicts peoples’ own experiences, or other sources of trusted information. For instance, a Russian construction worker told Der Spiegel that he was learning about casualties in Ukraine from Telegram, an online messaging service. “I know how many of our boys are dying in Ukraine,” he said. “They only lie on the television.” [2]

The fact that the construction worker believed his own social network over the television broadcasters is significant. It suggests the power of local, diffused networks to punch through official storylines.

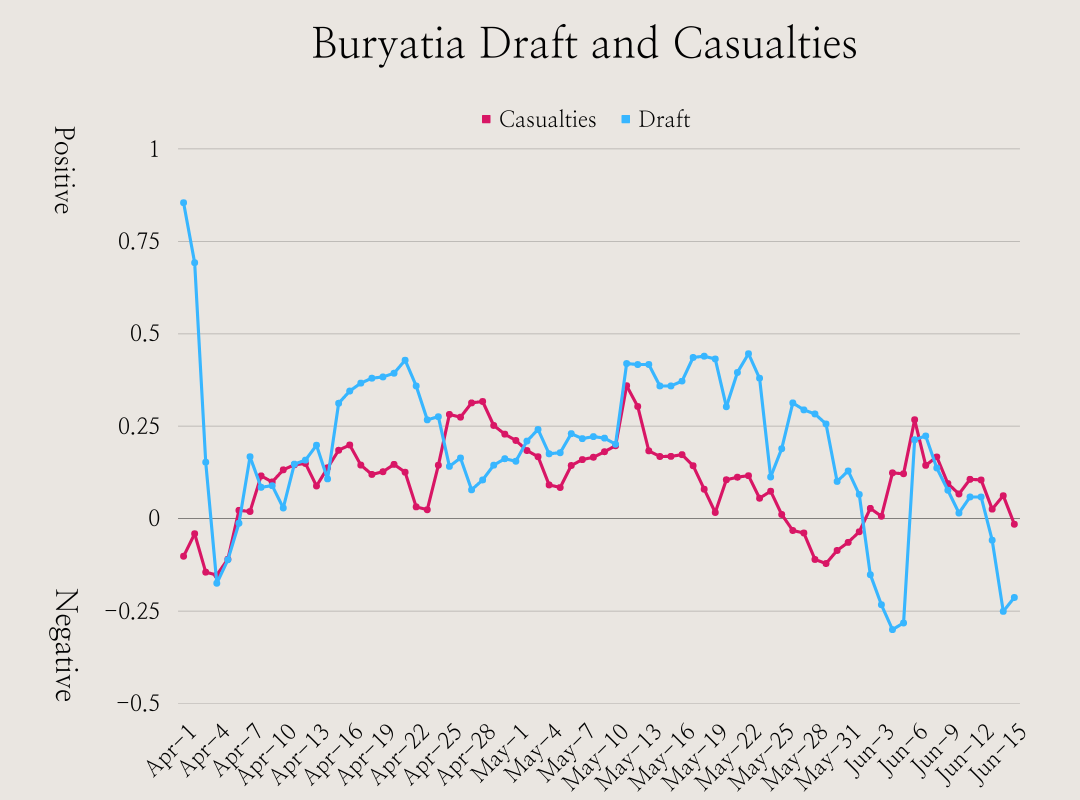

In fact, it appears that the more people in Buryatia hear about casualties on the front, the more skeptical they become. As FilterLabs.AI canvased online chatter in Buryatia, we found that sentiment toward casualties and the draft are starting to come together.

During its early propaganda pushes, the Kremlin was able to separate local feelings about casualties from feelings about the draft. However, starting in mid-June, sentiment toward the draft and casualties have started to move together. Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising. As a former soldier in Nizhny Novgorod told Der Spiegel, “The men are sent to Ukraine and come back in a zinc coffin.” No matter what one hears on television, funerals are hard to ignore.

The bad news, then, is that propaganda works. Concentrated media messages can boost sentiment toward something like a draft. But the good news is that it may not work for long. If other sources of information are available, many will believe them instead. This may especially be the case if their alternative sources of information are confirming what people are seeing with their own eyes.

Notes:

- Hebel, Christina. “High Casualties: Russia Pulls Out All the Stops to Find Fresh Troops.” Der Spiegel. June 15, 2022. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/high-casualties-russia-pulls-out-all-the-stops-to-find-fresh-troops-a-254bf9c2-c83b-4492-8dea-1f5cec53b03e

- Ibid