Detecting Discontent: A closer look at Russian coverage of the Israel-Hamas war

At an initial glance, Russian media appears to be a classic “closed system,” in which every source parrots the party line. Against a backdrop of widespread pro-government coverage, it can be hard to identify specific propaganda campaigns—and even more difficult to find and exploit dissent.

Difficult, but not impossible.

In its analysis of online discourse, FilterLabs.AI often looks for two things: conformity and anomalies. When sentiment surrounding a certain subject is trending hard in one direction—and doing so across media platforms—it suggests a coordinated information campaign, also known as propaganda. But when sentiment on a certain subject is moving against the grain, it suggests that someone, somewhere, is not with the program.

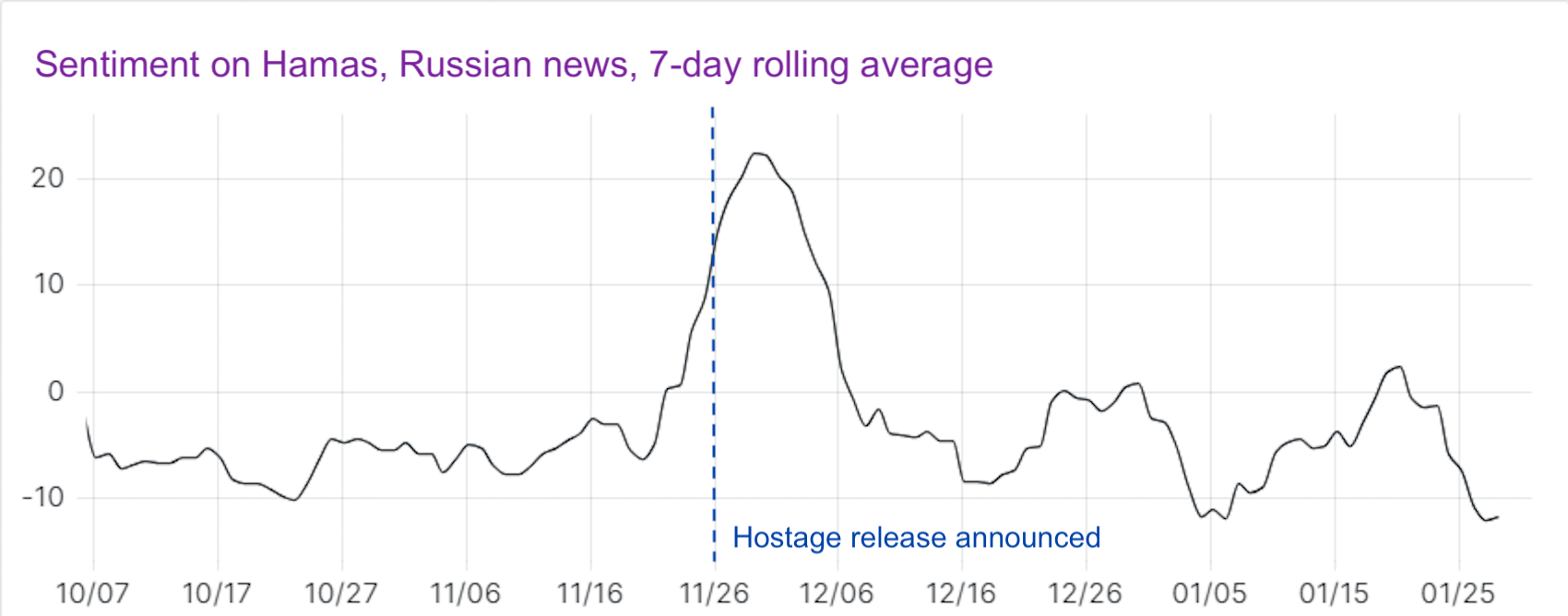

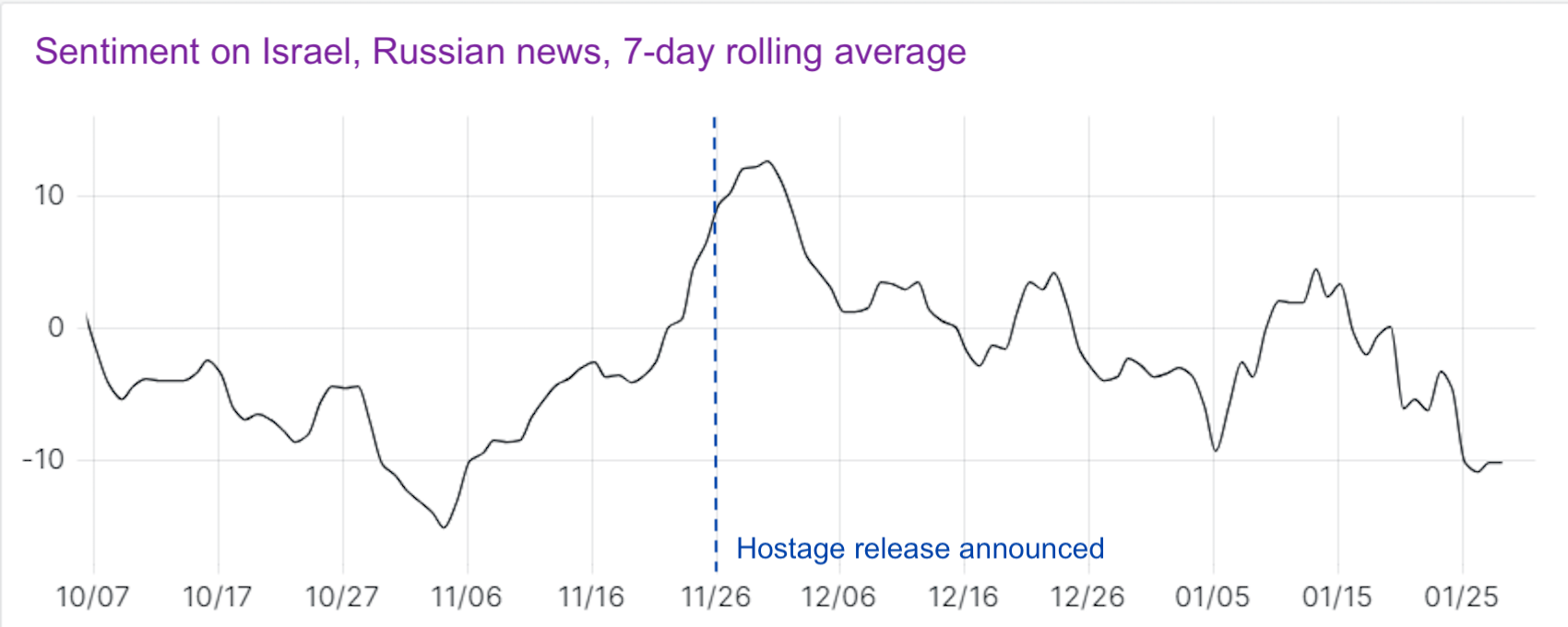

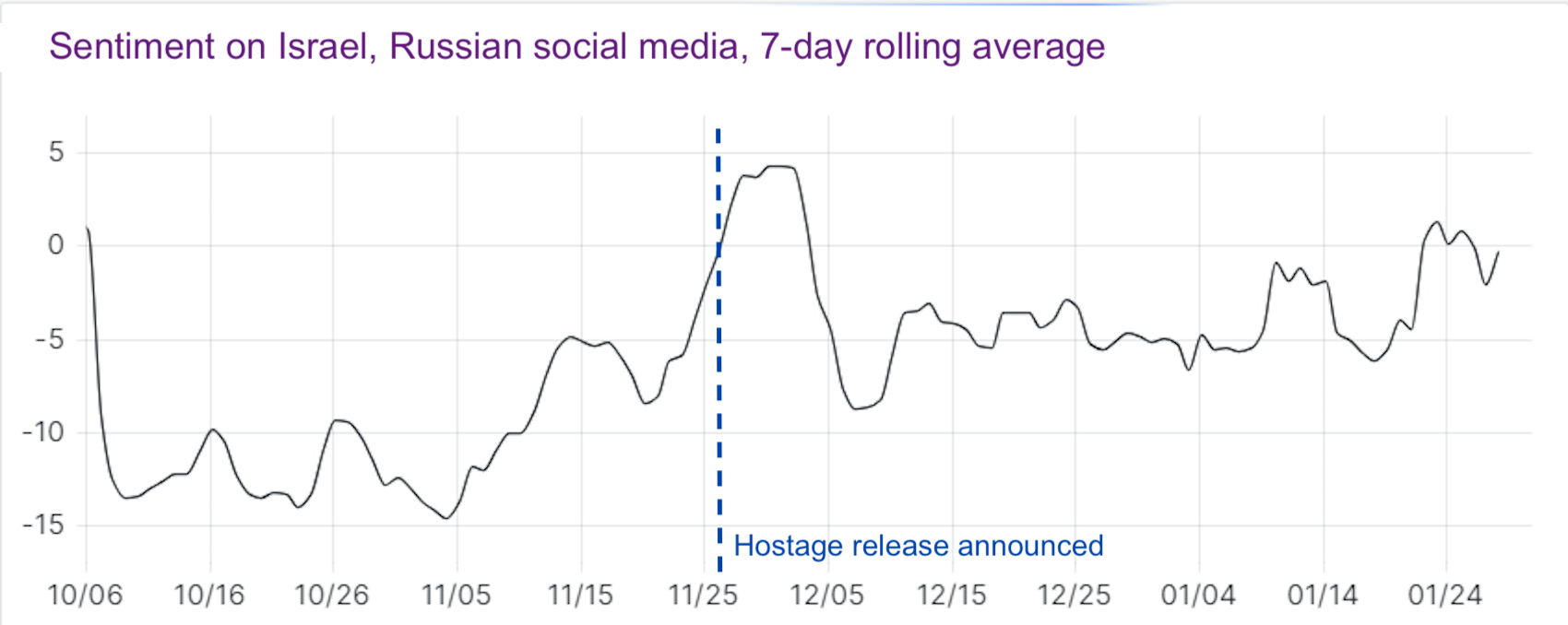

Near the end of last year, FilterLabs noticed good examples of both conformity and anomalies in Russian media. They appeared at the end of November, when Hamas released a hostage with Russian citizenship. Sentiment in Russian mainstream news articles that mentioned Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel, and Hamas, which had already been trending up, spiked even further. Coverage of Netanyahu and Hamas then quickly came back to baseline, while sentiment related to Israel remained higher than usual in the weeks following the announcement:

Most mainstream media in Russia is friendly to the Kremlin, if not directly controlled by it. When there is a massive spike in interest by the media in a certain story, it’s a fair bet that the Kremlin is pushing it. The hostage story fits the Kremlin’s overall interest in making Russians feel like they have an ongoing stake in the Israel-Hamas conflict, and that Putin’s diplomacy is bearing fruit. The hostage release almost certainly happened, of course, and it may have even been due to Putin’s intervention, but modern propaganda is less about creating events than it is about finding existing events and capitalizing on them by promoting them in ways that shape the narrative in a desired direction. The story made Putin look good, so naturally it got attention. Moreover, the positive shift in sentiment in the days before the release suggests that the Kremlin's information network was anticipating the event in its messaging.

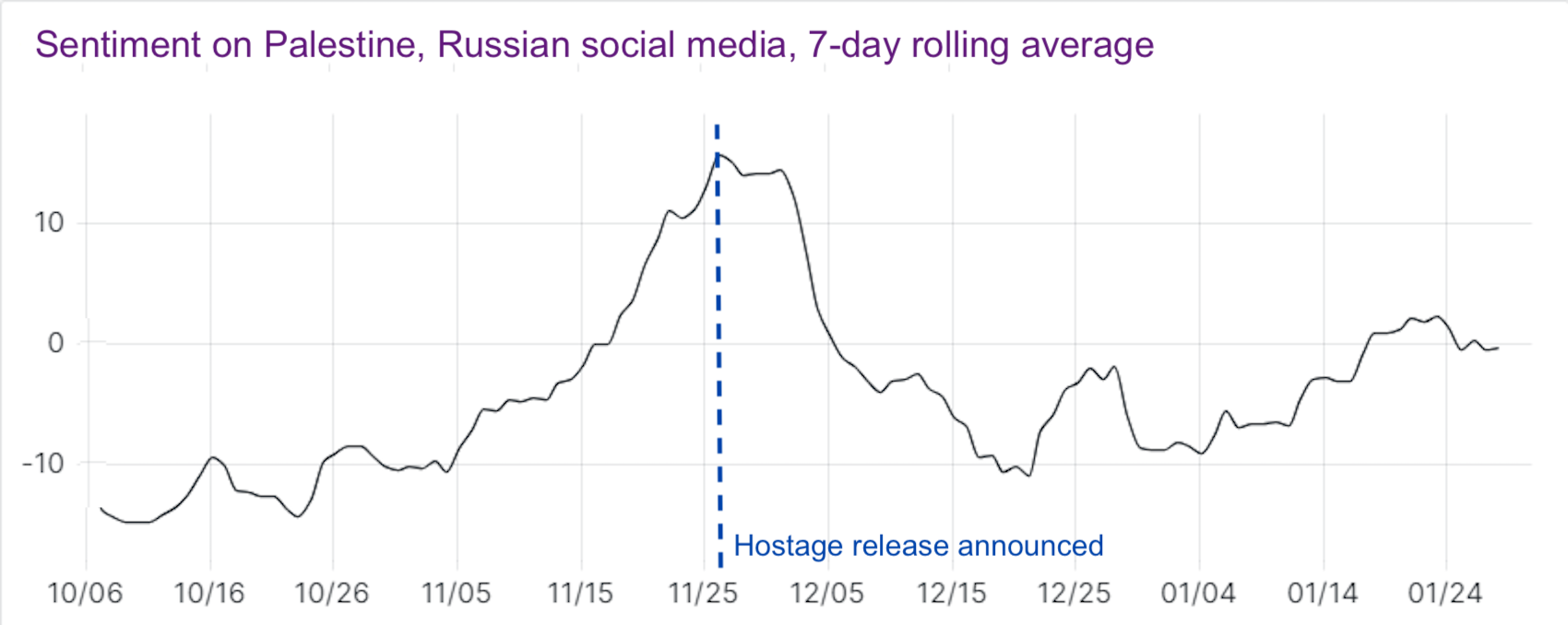

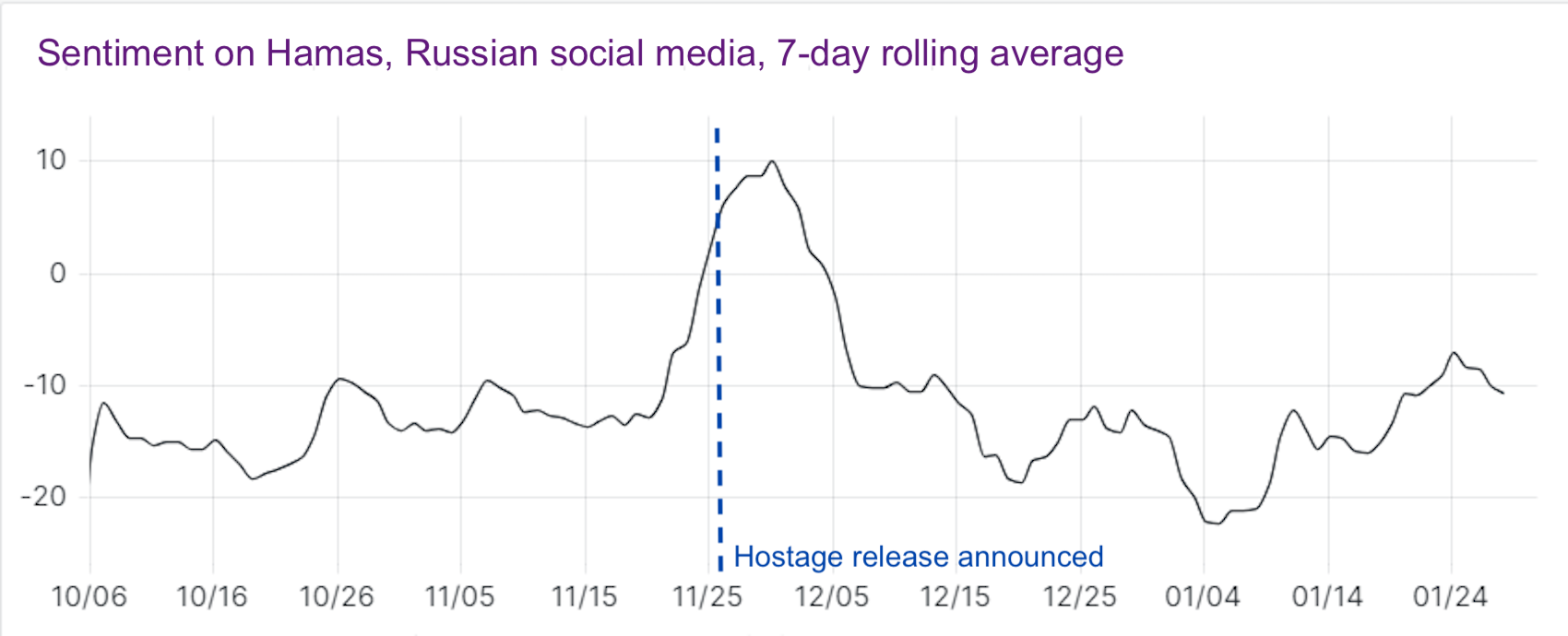

Further suggesting a propaganda campaign, FilterLabs found similar sentiment spikes around the same time in social media posts that mentioned Israel, Palestine, and Hamas:

Once again, posts about the hostages appeared everywhere, and were overwhelmingly positive.

Interestingly, the sentiment patterns look almost identical across platforms. Generally, mainstream and social media sentiment do not move in lockstep, so the similarity between the two sets of graphs should give us pause. The hostage story was always going to be popular, but this degree of unanimity suggests that the social media interest was not entirely organic.

It’s especially telling that once the story fades from memory, even for a few days, sentiment levels settle back to where they were before, both in the mainstream Russian press and in social media. The story was not part of a larger shift in public feeling. It served its purpose, and disappeared.

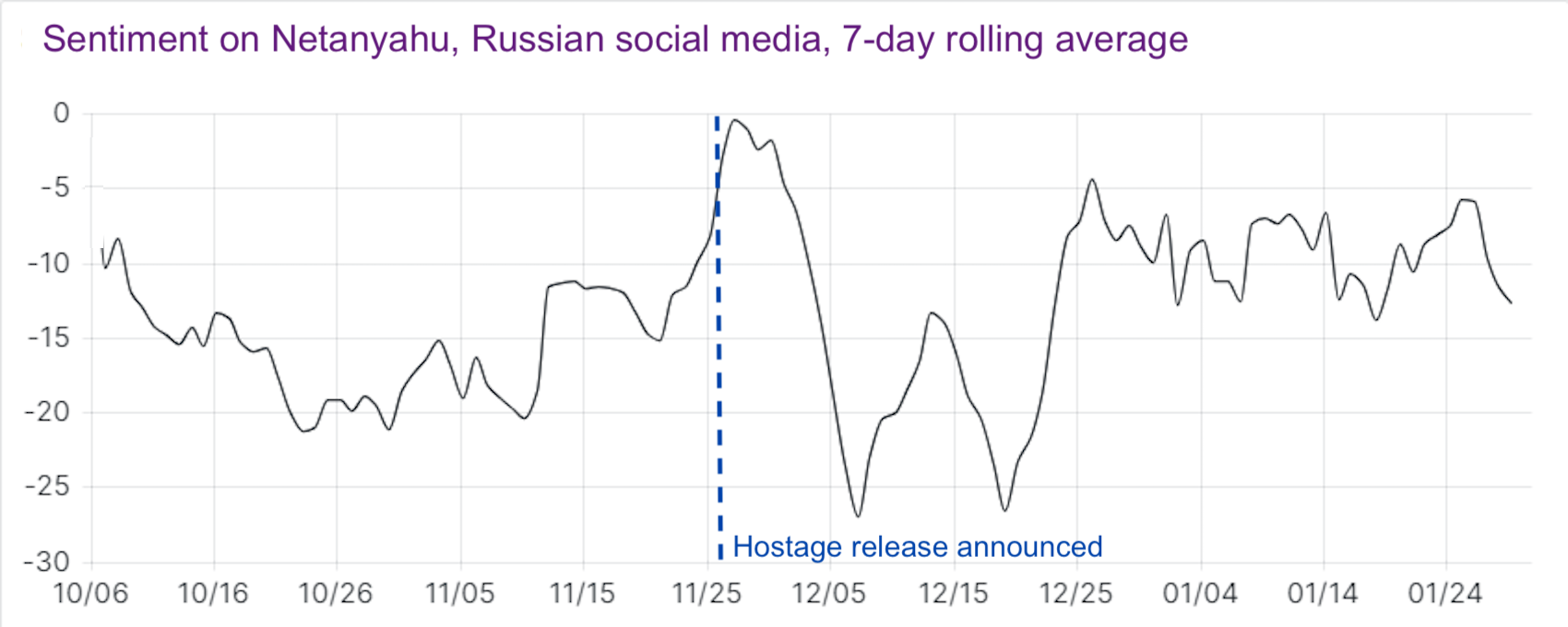

But there was one anomaly. Take a look at social media sentiment surrounding Netanyahu during this period:

One sees the same initial rise in sentiment, attributable to Netanyahu being mentioned in the feel-good stories about the released hostage. But then the sentiment graph starts to jump up and down instead of settling into place.

When FilterLabs looked more closely, something interesting emerged. Aside from stories about the hostage, there were also many posts about about the children of Netanyahu and other Israeli leaders who are serving in the IDF. The post authors were contrasting the Israeli politicians’ children—sometimes quite explicitly—with the children of the Russian political class, who are generally not on the front lines of the Ukraine war.

“Everything you need to know about patriotism” one wrote, followed by a list of Israeli officials’ children who had been drafted. Another post had a similar list and a sarcastic joke about Press Secretary Dimitry Pesokov’s daughter, who has a history of living large in Paris. “Where are the children of the Russian higher-ups?” asked another.

Other posts read:

- "Our ministers and deputies must be childless"

- "Are there sons of any of our officials fighting against Ukraine?"

- "Children of the Russian officials are just out partying, smoking and drinking..."

- "If you want to know what democracy and patriotism looks like—look at Israel!"

- "I want to ask the government officials whose countries are at war right now—where are your children?"

What can be learned from this online dissent?

First, it suggests that the Russian media ecosystem may not be as closed as it appears. Not all authoritarian countries are equally adept at creating a uniform media environment. It is much harder to imagine these criticisms on Chinese TikTok than it is on Russia’s Telegram.

Second, in order to find this dissent, one must know how to look for it. The mainstream sources will be uniformly pro-Kremlin, but many ordinary Russians still voice their dissatisfaction, albeit indirectly. Sentiment analysis can help here. If sentiment around a particular topic is moving one way, while related topics are trending in the opposite direction, it’s worth investigating further. A topic like “Netanyahu” may not seem to have anything to do with Russia’s internal politics, but in this case it acted as a proxy for how some Russians are feeling about their leaders.

Third, the Kremlin’s relatively loose control of social media opens opportunities for counter-messaging. It is extremely hard to change peoples’ opinions during wartime. To anyone who wants to convince Russians that Ukraine is in the right and they are in the wrong—good luck. But there may be opportunities to find and amplify existing discontent. In these posts, a fissure has opened up between the Russian political class and the families whose children are fighting the war.

It remains to be seen if someone can put this fissure to good use.